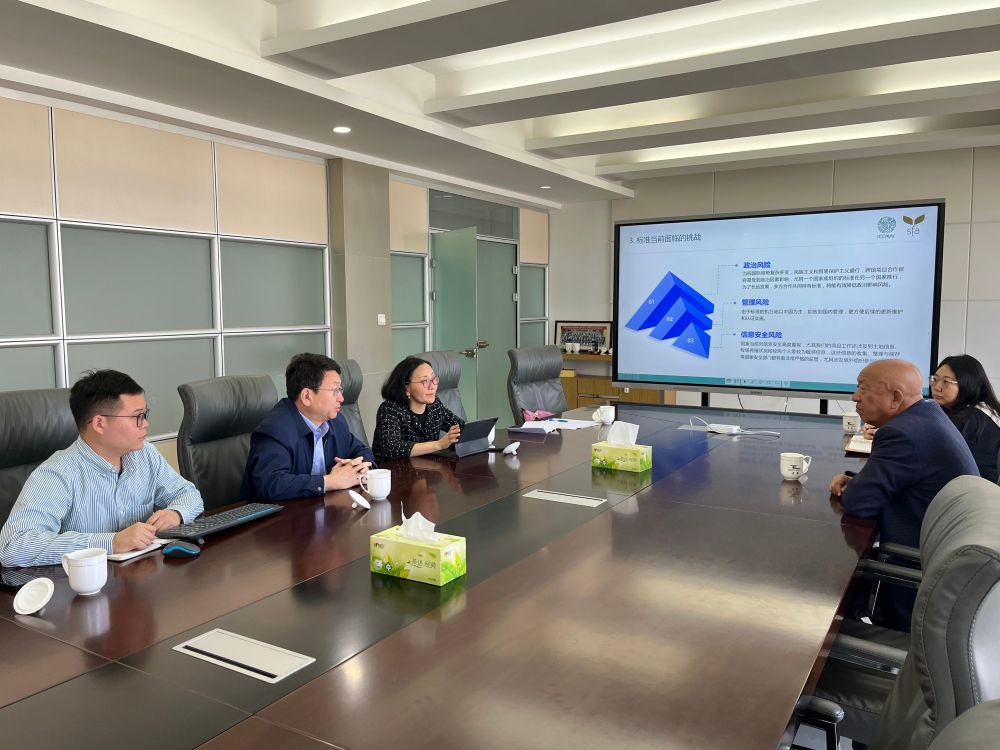

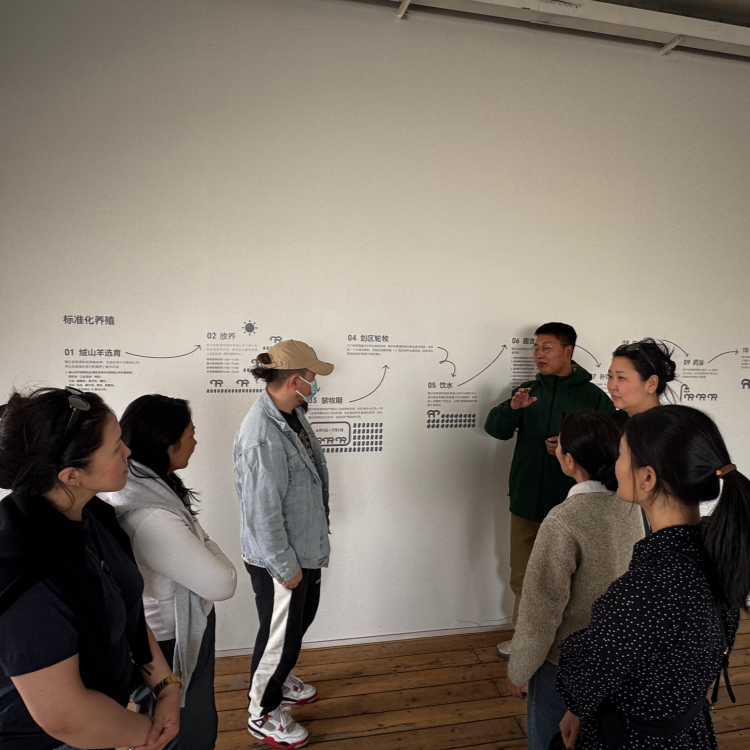

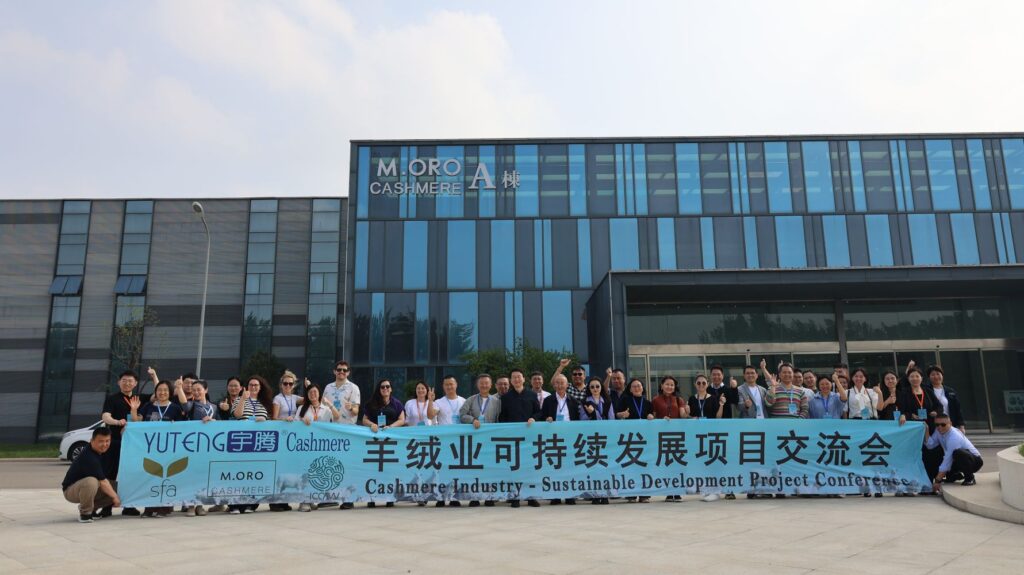

On 18 April 2024, a training seminar was successfully held in Beijing, China, bringing together representatives from Mongolian and Chinese certification bodies engaged in conformity assessment activities under the SFA standards.

Participants included representatives from the China Classification Society Certification Company (CCSC), the Mongolian branch of the SFA, the NART Training and Research Centre, and Nexus Connect LLC, among others.

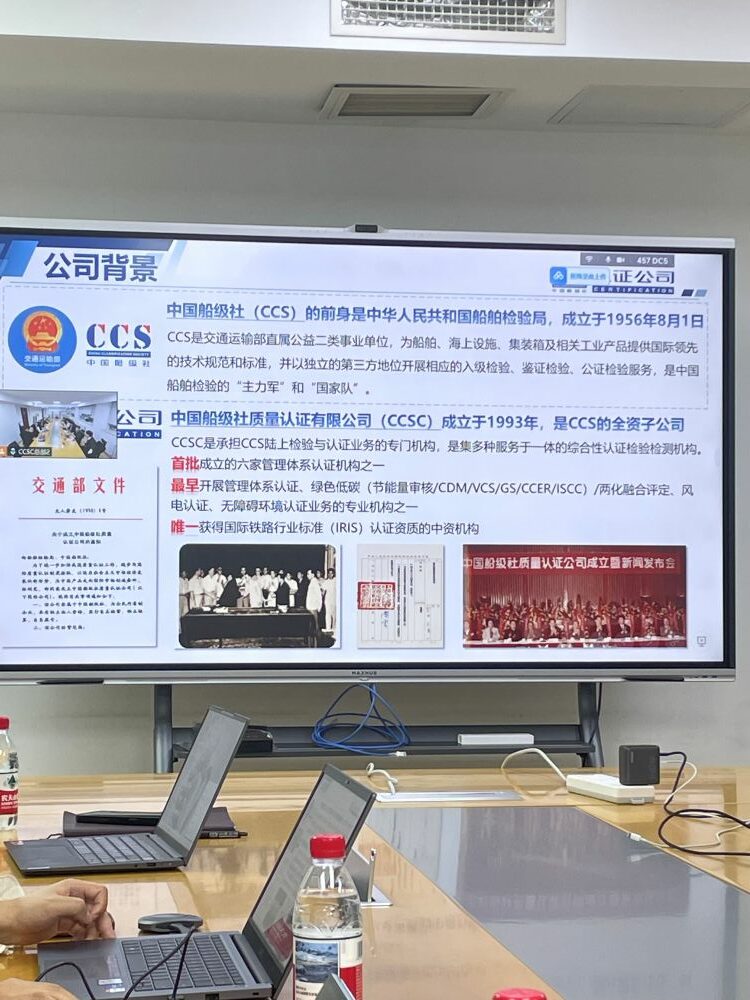

Experience of the China Classification Society Certification Company (CCSC)

During the seminar, the China Classification Society Certification Company (CCSC) shared insights into its extensive experience in certification of management systems, products, environmental and occupational health and safety standards, as well as low-carbon certification and standards for animal welfare and environmentally friendly production.

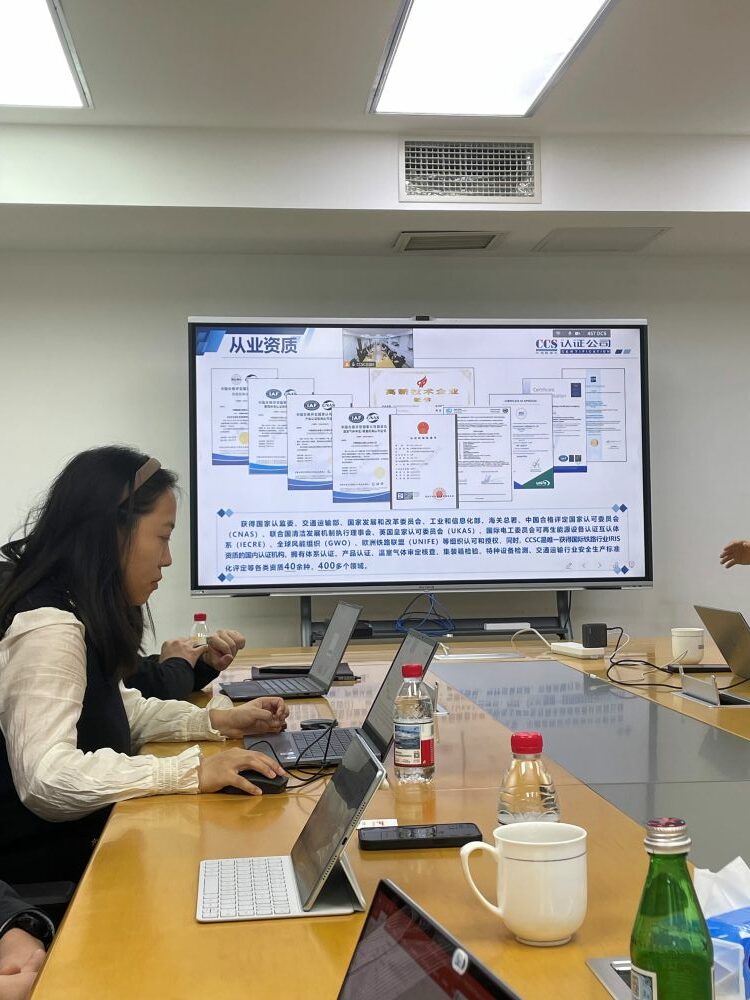

As one of China’s pioneering certification bodies, CCSC has operated for over 30 years in line with international standards. The company manages 32 branch offices, two subsidiaries, five professional centres, and one scientific research institute, offering over 40 types of specialised domestic certification across more than 400 sectors.

Furthermore, CCSC is the only Chinese-financed certification body in China accredited with the IRIS (International Railway Industry Standard), and is also accredited by CNAS, CCAA, and IECRE. The organisation places strong emphasis on scientific research and technological innovation, implementing numerous national and sector-level projects, including three invention patents, 20 utility model patents, and 12 software copyrights.

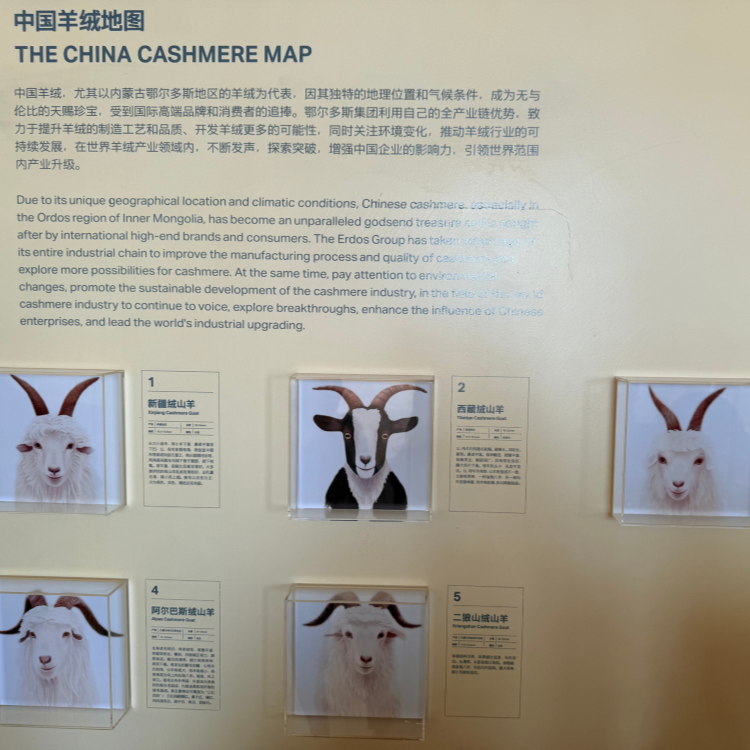

In addition, CCSC has formulated a quality service strategy aimed at enhancing its brand value on the international market. Since signing a cooperation agreement in 2021, CCSC has worked with the International Cooperation Committee of Animal Welfare (ICCAW) to assess 37,510 livestock farms across regions such as Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Tibet, and Liaoning, contributing significantly to the healthy and sustainable development of the cashmere sector.

At CCSC, certification is not viewed as a one-time assessment of compliance but as a comprehensive evaluation approach incorporating social responsibility, environmental stewardship, quality management, and innovation within the framework of sustainable development.

Mongolia's Engagement in the Implementation of the SFA Standards

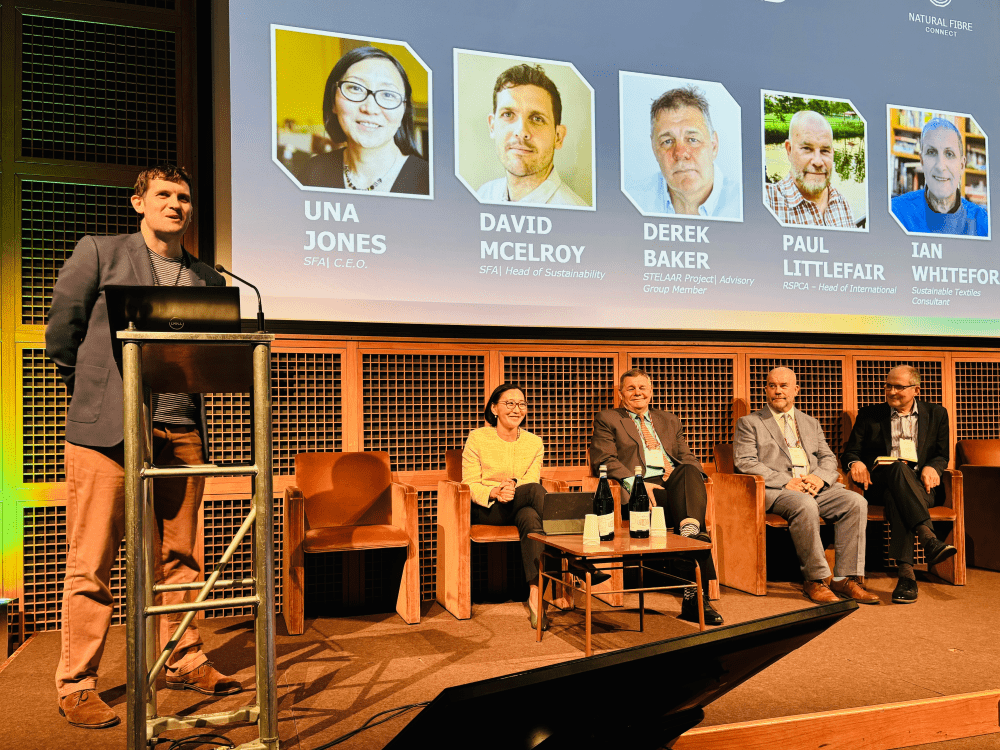

Mr S. Vandandorj, SFA Mongolia’s Country Coordinator, presented the progress of SFA standard implementation in Mongolia. He discussed the certification process and shared experiences from the two independent certification bodies operating in the country: SFCS and Nexus Connect LLC.

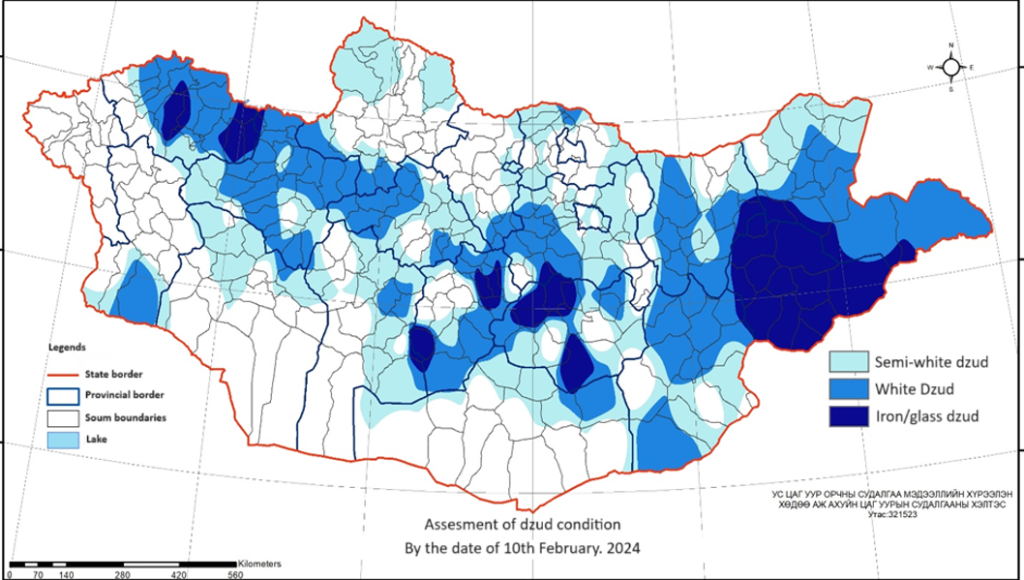

Currently, more than 20,000 herders from over 210 cooperatives across 130 soums in 17 provinces have been registered under Mongolia’s SFA framework. Participation in certification is voluntary, involving a three-stage evaluation—internal assessment, training, and conformity assessment—enabling integration into the “SFA Certified” cashmere supply chain.

To support this, the SFA in Mongolia, together with the NART Training and Research Centre, delivers both in-person and online training for cooperative leaders and herders. Ms J. Odgarav, training specialist at the SFA Mongolia office, highlighted the importance of accessibility, noting a shift from monthly virtual sessions to more direct, on-site training in recent years, addressing time and cost challenges.

Ms J. Odgarav also emphasised the vital role of local administrative support, indicating that the team holds meetings with provincial and district leaders to raise awareness of the standard’s significance during field visits.

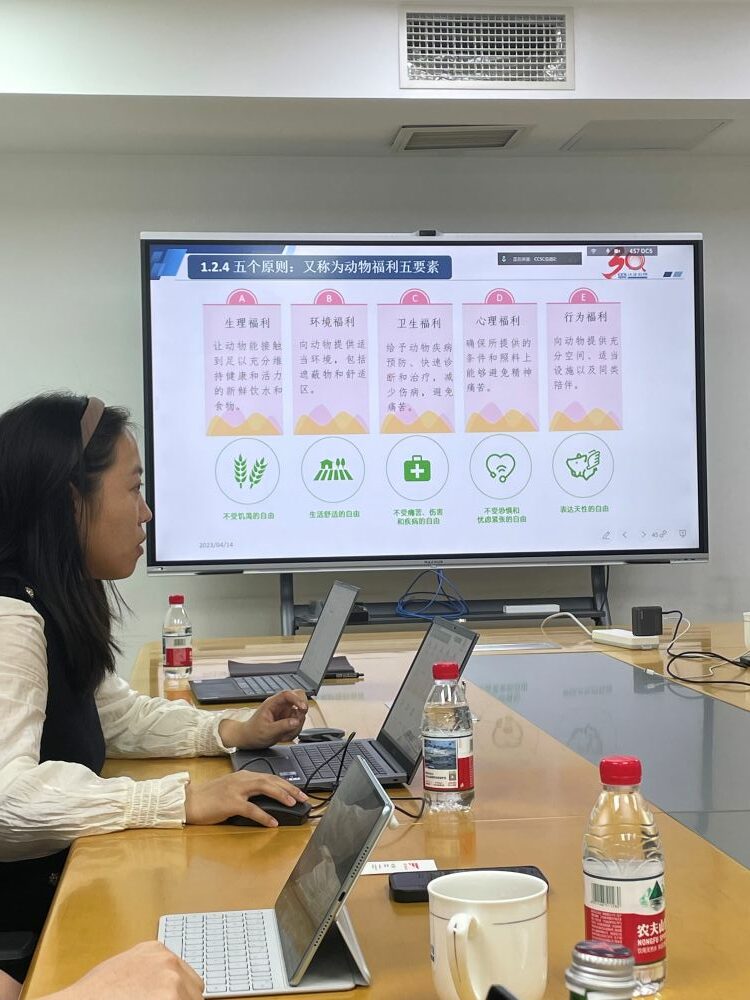

Launched in 2024, the SFA’s Animal Fibre Standard is a comprehensive framework comprising five principles and 26 chapters, aligned with international practices. The training currently being delivered aims not only to inform but also to prepare cooperatives to effectively implement these standards.

Capacity-Building for Herders: Practical Training Solutions

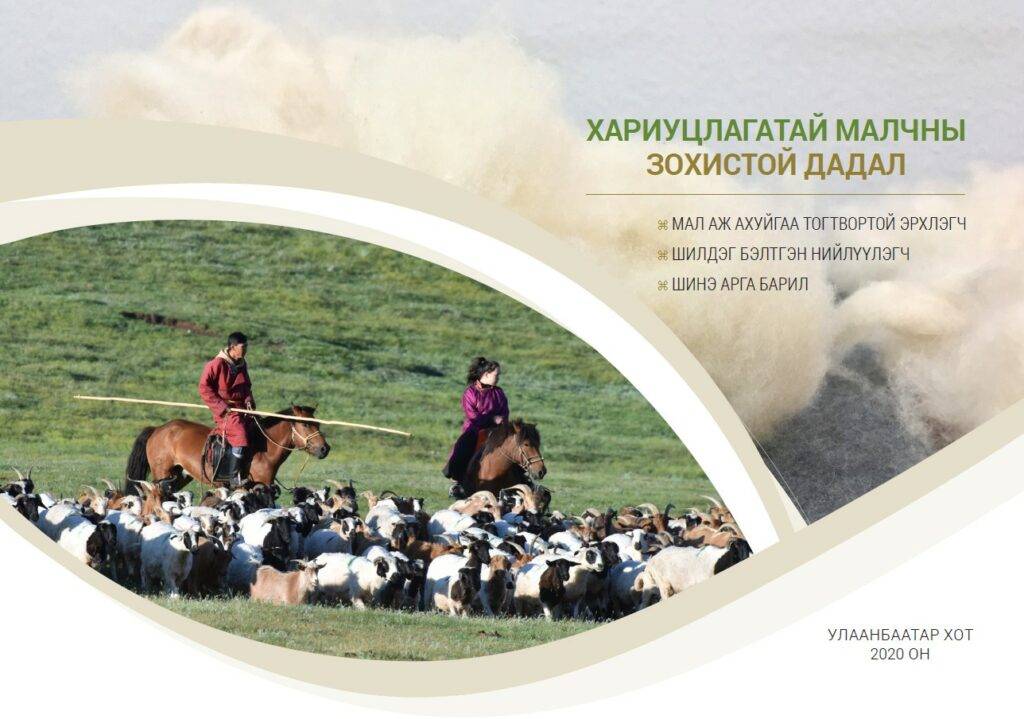

During the seminar, Ms S. Pagmadulam, Director of the NART Training and Research Centre, explained that the Centre delivers short-term, competency-based vocational training. NART is a certified professional training provider authorised by both the Ministry of Labour and the Ministry of Education in Mongolia.

In collaboration with the Mongolian Employers’ Federation and the Human Development Centre for Occupational Standards, and with support from the SFA, NART delivers training under the “Herder” Occupational Standard. These courses include:

- Sustainable Pasture Use: Equipping herders with knowledge on responsible livestock farming, carrying capacity, optimal pasture use, and increasing livestock productivity for economic gain.

- Small Ruminant Breeding: Covering the breeding of Mongolia’s 15 goat breeds, relevant state policies, animal husbandry, selection, and tagging.

- Small Ruminant Health: Addressing infectious and non-infectious diseases, preventative care, and collaboration with veterinary services.

- Cashmere Sorting: Teaching herders to sort raw cashmere by colour and carry out primary cleaning to meet processing requirements.

- Textile Processing Technician Training: Enhancing factory workers’ theoretical and practical skills for improved job performance and versatility.

Training outcomes are assessed by experts from the Ministries of Education and Labour, with successful candidates receiving official certification. Between 2021 and 2024, over 2,000 Mongolian herders received their certified “Herder” qualification.

NART also implements the “Young Herders of the New Century” programme in secondary schools. Supported by SFA Members and Scottish-based brand, Johnstons of Elgin, the programme fosters environmental awareness, traditional knowledge, and responsible citizenship among students.

Processing Industry Standards: SFA Clean Fibre Processing Standard (C003)

The SFA’s Clean Fibre Processing Standard (C003) provides a comprehensive framework for aligning Mongolia’s processing sector with international benchmarks.

Ms D. Bat-Enkh, lead certification specialist at Nexus Connect LLC, explained the audit process for implementing this standard. Factories must first register with the SFA, submit a self-assessment report, and then undergo a preliminary review to determine audit readiness. Nexus Connect LLC then conducts third-party audits to verify compliance.

Prior to the audit, factories receive full documentation—plans, expert assignments, and conflict-of-interest declarations—to ensure transparency.

The C003 standard includes nine sections and 88 criteria, covering occupational safety, HR management, supply chain traceability, quality assurance, environmental management, and production processes such as sorting, washing, and dehairing. Of these, 76 are mandatory and 12 are improvement-oriented.

Mongolian factories implementing this standard have demonstrated notable progress, particularly in workplace safety. Many display clear safety guidelines near equipment, maintain risk assessments, and conduct emergency preparedness training. Information boards and regular safety instructions are also common practice.

Environmental compliance includes proper storage, transport, and disposal of chemicals, use of designated facilities, and energy efficiency initiatives. Green space development and restoration activities are also recognised during audits.

The human resource management criterion plays a crucial role in shaping the internal culture and ensuring the sustainable operation of processing plants. Factories are increasingly focusing on HR practices by ensuring that employees receive regular medical check-ups, are covered by accident insurance, and that labour relations align with human rights conventions and international standards.

The requirements under the supply chain management criterion focus on evaluating the level of collaboration, transparency, information flow, and traceability systems between processing factories and raw material supplier cooperatives. The aim is to assess whether an integrated and transparent partnership framework exists throughout the supply chain.

In the area of quality management, factories are required to register raw cashmere from the point of origin, conduct quality control at every stage, and undergo quality evaluations by independent certification bodies. Assessments also consider whether laboratory environments and the methods used are in line with international standards, accredited, and capable of producing reliable results.

Environmental management is not merely a component of the standard, but a genuine benchmark for measuring a factory’s commitment to responsible operations. Factories are implementing policies to improve energy efficiency by monitoring usage and introducing control systems. At the same time, they focus on waste sorting, recycling, and wastewater treatment. Special attention is given to the safe use, storage, and disposal of chemicals. Initiatives aimed at increasing green spaces and undertaking land rehabilitation projects are being actively implemented—efforts which are often highlighted during standard audits.

During the scouring, dehairing, and sorting stages, factories are expected to continuously monitor and upgrade the productivity of machinery and equipment. They must ensure staff are professionally trained at each step and that technological procedures are strictly followed. Verification of full standard implementation includes the documentation of product origin, induction training for new staff, and compliance with safety protocols.

Supply Chain and Traceability Standards

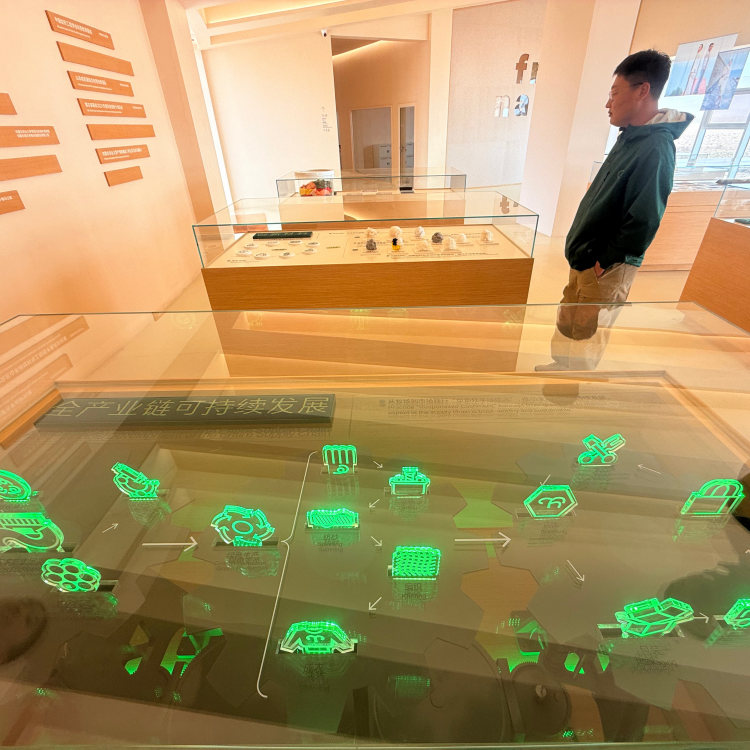

Factories and certified cooperatives meeting the Clean Fibre Processing Standard undergo SFA traceability audits. The traceability system rests on three core standards: the SFA Animal Fibre Standard (for herders), the SFA Clean Fibre Processing Standard (for factories), and the SFA Chain of Custody Standard (for the supply chain).

Meeting all three ensures the production of certified, traceable, and responsibly sourced clean fibre products, contributing to the development of a transparent and sustainable supply chain in Mongolia’s cashmere sector.

Translated by Tamir Bud

SFA COMMUNICATIONS OFFICER

9 June 2025

Originally posted on 12 May 2025: https://sustainablefibre.mn/cab-traning-exchanges/