In 2022, on behalf of the SFA, María E. Fernández-Giménez with the assistance of Tugsbuyan Bayarbat, Chantsallkham Jamsranjav and Tungalag Ulambayar hosted a series of participatory workshops with women herders from Mongolia’s Arkhangai and Bayankhongor provinces. Discussing what decent work meant to them, the sessions looked at how women herders relate to their work – characterised by a connection with nature, their herd, the family unit, their community and the wider Mongolian population.

What does decent work mean?

Broadly speaking, it relates to employees earning a sufficient income from the work they do in a fair and safe environment, and while it might have different meanings depending on geography, culture and economic development, the term decent work is somewhat rigid in its definition. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) defines decent work as “productive work for women and men in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity”, with the four pillars of their Decent Work Agenda – employment creation, social protection, rights at work, and social dialogue – pivotal in the development of The United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs); Goal Eight is Decent work and Economic Growth.

Access to decent work is one of the Five Global Principles of the SFA’s Cashmere Standard and ensures ‘fair hiring practices and working conditions, equality in wages, the protection of traditional communities, the prevention of child labour, gender equality and the promotion of health and safety’. The Principle is also guided by the eradication of forced labour, while ensuring equal pay and decision-making roles for women. Developed inline with the ILO’s own definition, the SFA’s Decent Work Principle often applies to communities that live in remote, rural locations which can be a regulatory challenge. However, conversations across the supply chain are important in addressing such challenges, as they capture the realities of herders’ working lives. They also provide vital insight for standards such as the SFA’s by contextualising the nuances of herders’ own definitions of decent work within their day-to-day – something that might not necessarily be captured by international development agencies.

Conversations from the workshops highlighted two overarching themes: the definition of what decent work meant to the women in a practical sense, and how the societal expectations impact the women’s access to it. The facilitators used themes inline with, but not exclusive to, the ILO’s Decent Work Agenda to discuss their definition of decent work. This covered the women’s opinions on meaningful and productive work in healthy and safe environments, as well as freedom from abuse, harassment and discrimination, social protection and security, social dialogue, cooperation and opportunities for professional development and learning.

It’s widely accepted that herding in Mongolia is more than just a livelihood, it’s a way of life that brings meaning, a sense of identity, culture and tradition – it’s an occupation that creates feelings of dignity, pride and purpose – especially when the work is valued and respected by the wider society; an important component of the global understanding of decent work. Discussing the position of herders in modern Mongolia, the participants noted how respect for herders and the herder lifestyle had dwindled in recent years, with young people increasingly opting to live in urban areas in pursuit of life away from rural pastoralism. According to The International Organization for Migration (IOM), this is a countrywide shift, with dramatic rural-to-urban migration raising the capital Ulaanbaatar’s population to almost 1.5 million – half of the entire country’s total population. With this migration, the women feared the loss of their culture and tradition, emphasising a lack of cultural education and a disconnect between those living rurally and in urban environments. The development of a more secure rural economy was just one of many suggestions the women made in reference to not only encouraging people back to the countryside, but also as a means to secure productive work and income year-round from their livestock. They also touched on the prospect of alternative rural employment as another solution. Interestingly, the women intrinsically linked decent work and productivity, raising a further five points that they thought vital to their access to both:

- Stable and sufficient income from livestock.

- Access to the means of production (seasonal pasture lands, water and minerals, shelters and corrals (animal pens) and livestock).

- Access to the knowledge and the information they needed to work.

- Fair and timely pay for hired herders.

- Protection from climate hazards.

It’s important to understand that cashmere is just one of several income streams for Mongolian herders who herd a mix of goats, sheep, cattle, camels and yaks – dependent on their geography. The mixed herds provide a range of produce ranging from cashmere fibre to meat and dairy, and generate seasonal income throughout the year. As Mongolian herders are predominantly reliant on this produce, access to resources and means of production is paramount to their access to decent work year round. A great example of this was discussed by the workshop participants from Arkhangai. The women spoke of their relative success in adding value to their produce through the production of ‘fancy’ aaruul (a traditional Mongolian curd cheese) which they sold directly to customers in the capital and other cities across Mongolia. They keenly noted that aaruul, along with sales from other such value-added dairy products, accounted for roughly 80% of their household income. In a later discussion regarding the production of value-added produce and their access to opportunities for professional development and learning, the women all strongly desired increased access to vocational training, forums and knowledge sharing in order to independently improve the earning potential of their produce.

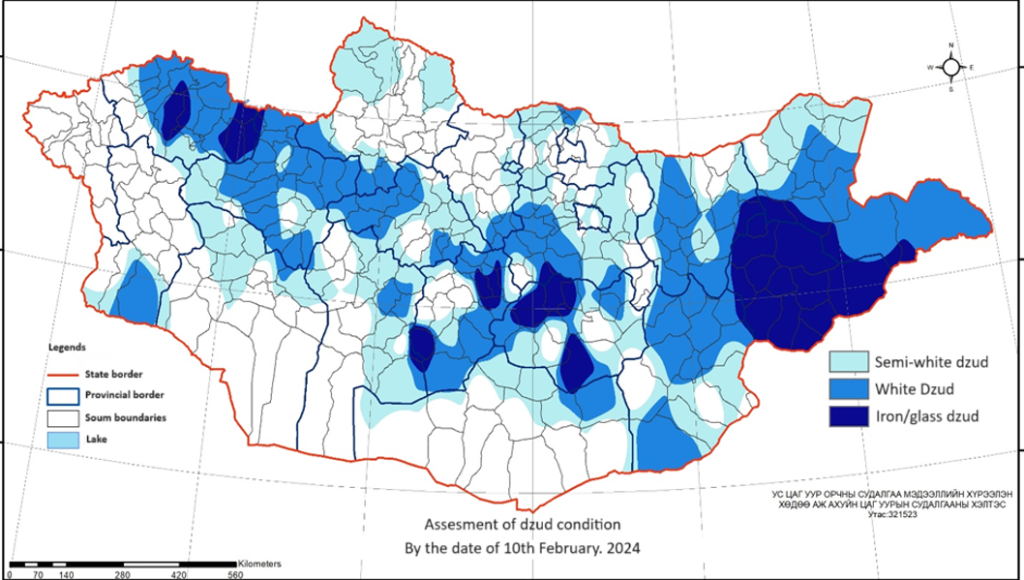

Another important factor that sits front and centre of both international and more localised decent work agendas is the impact of climate change and the realities of its effect on rural pastoralists. With a changing climate, fragile ecosystems, such as those seen in Mongolia, are already dealing with the brunt of more extreme weather. According to Save the Children, Mongolia is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change, with a significant rise in dzuds – catastrophic weather events when a drought in the warmer months is followed by extreme temperature drops and snowfall. In the past, dzuds were known to occur once every decade or so, however in recent years they have become much more common. The National Agency of Meteorology and the Environmental Monitoring (NAMEM) of Mongolia reported that as of February 2024, a total of 80% of the country has been in a dzud weather disaster, with iron- / glass-dzud hitting regions covering 58 soums, across 13 provinces of Mongolia. The snow fall, along with the fatally low temperatures, restricts livestocks’ access to food, creating significant challenges for herders. When discussing the impact of dzuds, long term weather forecasts was one way the participants said could help them in their preparations, with the groups all in agreement that such pre-warnings would allow them to stockpile hay for the animals, as well ensuring appropriate access to shelters.

While much of the discussions focused on the welfare of the land and livestock in the herder context, the women also spoke of the challenges they’d experienced with their own and other’s health and safety whilst working – a core component of the Decent Work Agenda. The ILO’s International Labour Standard on occupational safety and health states the importance of how ‘workers must be protected from sickness, disease and injury arising from their employment’. It also understands that this might not be the case for millions of workers worldwide – with some difficulties arising when the lines are blurred between the workplace and home and when income streams are seasonal. Using cashmere as an example, cashmere is harvested in the spring, over a course of a few months. Within that period, tens of millions of goats across the country are harvested for their fibre. This level of intensity can create a number of challenges with respect to health and safety, especially as the home and workplace, as previously mentioned, are one and the same. The women spoke about a number of issues including the importance of ‘safe and healthy working conditions that promote mental wellbeing and limit excess stress’ as well as ‘ensuring the work is appropriate for the ability and age of the person doing it’. The women, especially those from Arkhangai, expressed how taking time away from work and vacations played an important role in the reduction of workplace stress, especially as all the women agreed about the impact of their ‘triple labour burden’ – caring for the livestock, children and the elderly, the processing dairy products and housekeeping. It’s customary for children, especially adolescents, to support their family by helping with milking, cashmere harvesting and the processing of products from the animals, alongside caring for younger siblings. The workshop participants, worryingly, identified how children, especially boys, were increasingly being removed from school too soon in order to do so, thus not finishing their education. With respect to decent work, many of the women mentioned the importance of education for children, especially how the education of their children in soum centres (a community and commercial centres with access to facilities, education and commercial opportunities) played a significant role in their development. Soum centres have dormitories for children to attend school, however if those spaces are full, the women are expected to stay with the children, which was noted to potentially create marital stress. As the family and labour unit are the same, this can often lead to children being educated at home – another addition to the triple labour burden.

Another important factor raised by the participants was how the triple labour burden impacted their ability to access health care, due to time constraints along with a number of other obstacles. Some noted how health insurance was too expensive for them, while most of the women complained about how health care was not readily available, with doctors appointments difficult to obtain. They also discussed how they didn’t have confidence in the training of the bag (a smaller division of the soum) and soum doctors available to them – with many expressing worry about mis-diagnosis and dismissals of their symptoms. This, combined with their remote locations, presented a very real concern for the women, especially with respect to access to vaccinations, regular check ups and other preventative care and screenings.

In the context of community cooperatives and collectives, women across the various groups emphasised the critical need for organisations representing herders’ rights. These organisations would address pressing issues such as the loss of grazing lands, environmental degradation, inadequate access to health and veterinary services, and the absence of preschool facilities in remote rural areas. Particularly, they underscored the necessity for representation specifically tailored to women herders. Due to the triple labour burden the women highlighted the profound social isolation they sometimes experienced. They also expressed a desire for increased opportunities to participate in community and cultural events, seeking avenues for social connection and engagement. There was also a recurrent observation regarding the shift in herder culture towards individualism, which they saw to have eroded traditional forms of community solidarity, collective work, cooperation, and mutual support. While some communities still maintain these traditions, others have experienced a decline, impacting both local and global perspectives on accessing decent work opportunities. These observations underscore the importance of revitalising and preserving communal values to foster more inclusive and sustainable decent work for women herders.

The insights gleaned from discussions between the workshop facilitators and the women herders immediately shed light on something interesting. In terms of the ILO’s approach to decent work, which is categorised under somewhat rigid frameworks, the women herders held a more holistic perspective on what constitutes decent work. From their perspective, decent work relied heavily on the interdependent integration of human, environmental and livestock health and wellbeing.

The participants emphasised the importance of:

- The health of the environment in which they do the work.

- The health of the livestock on which their livelihoods depend, and which in turn depend on a healthy environment.

- Human health and wellbeing – which is also linked to the two previous points.

These points prompt reflection on the potential gap between global standards and the realities and requirements of herders, especially women, in Mongolia’s countryside. However, it also offers an opportunity for organisations like the SFA, which use international standards to craft their own standards, to develop an approach to decent work that makes use of insights from both ends of the spectrum.

Learn more about how the SFA incorporates decent work practices into their standards here.

Lotti Blades-Barrett

8 March 2024