What makes cashmere a luxury fibre and why it’s important to protect its supply chain

Despite its luxury status throughout the centuries and its consistently high price tag, the past few decades have begun to see a dramatic change in the availability and affordability of cashmere fibre. What was once a statement of high-end fashion now can be found at nearly any price range, showing up in fast fashion retailers and online shops for sometimes less than £50. Why has this happened, and what does it mean for the future of cashmere? To understand the impact that falling prices and mass production has had on the cashmere supply chain, the environment, and peoples’ livelihoods, it is first important to understand what cashmere is, where it comes from and what makes it such a sought-after fibre.

Coveted by royalty and the upper-class

Cashmere has triumphed its way through history as the world’s most luxury fibre, having been prized by royalty, popularized by Napoleon, and made available to consumers by the finest fashion brands of the times. The material’s biggest emergence in Europe occurred in the late 18th century when it became coveted by upper-class women in Britain and France (The Independent). Not long after, in the 19th century, Beu Brummel, arbiter of men’s fashion and iconic gentleman of England, made white cashmere waist coats a popular garment for sophisticated gentlemens’ style (The New Yorker). As time went on, cashmere remained a fashion staple for both men and women but gradually evolved from use in shawls and waistcoats to jumpers, cardigans, and other knitted garments. This shift happened largely during the knitwear revolution in the mid-twentieth century and especially in the 80’s when fashion designers like Shirin Guild began using cashmere alongside sheep’s wool to make dresses, suits and other clothing items (The Independent).

What is cashmere, exactly?

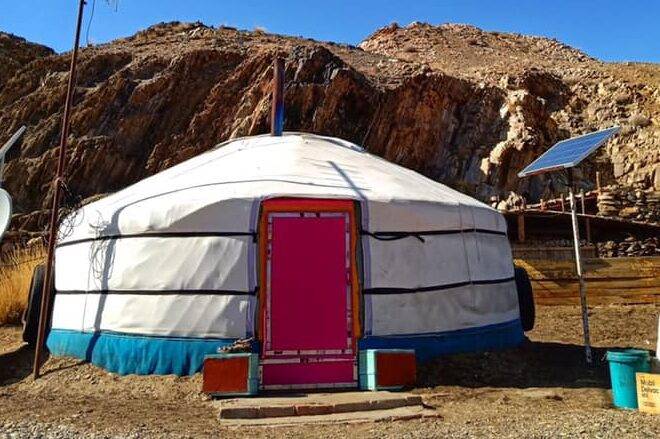

Cashmere is a type of wool that comes from the downy undercoats of cashmere goats and is distinct from the goats’ course, outer layer of hair – or ‘guard hair’. While many goats grow this undercoat, some have been selectively bred for cashmere production. The quality and yield of cashmere fibre is affected by diet, gender, age, and climatic factors. Herds from the arid regions of Inner Mongolia (China) and Mongolia, are considered to produce the finest cashmere fibre in the world and are the top two producers. Herders in these regions are historically nomadic and have been guiding herds of goats and other livestock across the grasslands for thousands of years – although herders in Inner Mongolia have now shifted to more farm-based production. In fact, Mongolia is so uniquely suited for cashmere production that its production supports nearly 40% of the country’s population. It is also important to note that the life of a cashmere herder, though challenging, is one traditionally respected and enjoyed. Herders feel a sense of commitment and connection to the land and goats and, given prices remain stable, it is a life they would proudly encourage for their children.

As for the fibre itself, cashmere is fine in texture, strong, light, and soft. Under the U.S. Textile and Wool Acts, which closely reflect regulations in other regions, a wool or textile product may be labelled as containing cashmere only if 1) the average diameter of the fibre does not exceed 19 microns; 2) the product does not contain more than 3% (by weight) of cashmere fibres with average diameters exceeding 30 microns; and 3) the average fibre diameter may be subject to a coefficient of variation around the mean that shall not exceed 24%. For comparison, a human hair can range from 17 to 181 microns in diameter. By industry standards, cashmere must be at least 0.6 – 2.54 centimetres long.

What makes cashmere a highly desirable and versatile fibre

Chimaeze Onyeiwu, Procurement and Technical Director at Johnstons of Elgin, a Scottish textile manufacturer that specialises in cashmere and fine woollens, describes the qualities of cashmere fibre: “Apart from the much recognised softness and fineness of cashmere, it is also hydrophilic, hygroscopic, hypoallergenic and has a very good crimp. Hydrophilic means it naturally absorbs water, which makes it an easy material to dye. Hygroscopic means the cashmere actively attracts humidity from the air which gives it a high moisture content and allows it to regulate insulation properties to fit the weather. Crimp relates to the waviness of the fibre, which helps to trap warm air between the fibres, creates bulk or loftiness, and helps offer insulation up to 5 times that of wool. Add to this its natural hypoallergenicity (non-irritating), its extensibility (extendable), its natural range of colours, and you have a highly desirable and versatile fibre.”

It is not always obvious at first touch whether a consumer is buying a high-quality product – but there are a few things they can look out for. First is the tension in the knitting – if a small section of a cashmere garment is stretched, its ability to bounce back into shape quickly indicates higher quality. Another trick is to hold the material up to the light and see how transparent it is. The better the cashmere, the denser the material will be. While a certain degree of pilling is considered normal for cashmere garments, a large amount indicates low-quality. Finally, consumers would do well to be sceptical of softness as this may indicate over-processing or that the cashmere has been blended with synthetic fibre. More expensive cashmere is more often harder in the store but will improve and become softer with age and hand-washing (The Sceptical Shopper).

Low quality cashmere is a modern phenomenon

The cashmere production process begins at the herder level in the Spring when goats naturally shed the downy undercoat which keeps them warm during winter. In Mongolia, harvesting is carried out by carefully combing the goats to help remove the moulting cashmere, while in the Inner Mongolia region of China shearing is more commonly used. After harvesting, the fibre is sorted by colour, bagged, and sent on to processing plants for scouring and dehairing. This is where the raw fibre is washed to remove grease, vegetation, and dirt and then dehaired via machinery to remove any remaining guard hair from the fine cashmere fibres. The fibre is then spun into yarn and dyed before being woven or knitted into a sweater, scarf, or other final garment.

Ian Whiteford, Sustainability and Compliance Manager at Alex Begg & Co., a Scottish weaver of luxury accessories, reflects on the process: “In order to obtain finished articles of the highest quality, it’s vital to start with the very best raw material then to carefully manage the production process.” Even if the raw material is of the finest quality, a sub-par finishing process can affect the final product’s look, feel, and touch. Whiteford continues: “These [processes] impose mechanical stresses, involve chemicals such as detergents and dyes and subject the cashmere to high temperatures. In the end, however, all this effort and expertise creates products of exquisite softness.”

Skill and precision are needed to protect the quality of this fragile fibre as it travels along the supply chain. Cheap, lower quality cashmere is indeed a modern phenomenon as growing demand has resulted in a speedier production process that is more likely to damage the fibre along the way. Not only is cheap cashmere reflected in the quality and longevity of the garment, but it also threatens the future of the sector, after all who is going to train to develop the next generation of skilled craftsman, when the demand is for cheap and low quality? That is before we consider the impact on the herders and the environment.

The effects on herder livelihoods and the environment are profound

According to USAID, over the past few decades the garment industry has rapidly transformed: prices have steadily decreased while the fashion cycle has accelerated. Consequently, the market size for luxury clothing is declining and the bargaining power in the value chain has shifted from producers to brand name holders. Competitive pressures from garment producers in low-wage countries have also forced producers in high-wage countries to use faster equipment – which, for cashmere, comes at the cost of quality (older and slower machinery can sometimes be better at protecting the fibres). Despite these changes in the supply chain, it is unlikely that cashmere will ever go out of favour with designers. In fact, its widespread availability means it is now more accessible than ever to the masses (The Independent).

The effects of these industry changes on the environment, herder livelihoods and animal welfare are pronounced. The lower the market value of raw fibre, the higher the pressure to maintain a large herd to ensure a viable income. This in turn puts pressure on the rangelands, and coupled with the effects of climate change, contributes to desertification and loss of biodiversity. If herders in Mongolia are unable to support their families through cashmere production, they are left with few options for alternative income sources and may need to move to the slum-like outskirts of towns and cities – a migration we are sadly already witnessing in Ulaanbaatar.

The SFA is working to create a more responsible cashmere supply chain

It is increasingly important that measures and programmes are put into place to protect the integrity of the cashmere sector, stabilise prices, and return to more sustainable grazing practices. The Sustainable Fibre Alliance (SFA), an international, multi-stakeholder NGO working with herders in both Mongolia and China, created the world’s first global cashmere standard for this purpose and has been working closely with members, local government and other industry partners to make a more resilient and responsible cashmere supply chain. Through the SFA Cashmere Standard and associated codes of practice, it helps to ensure that fibre is produced according to high animal welfare standards and in a way that protects rangelands and secures the long-term viability of herder livelihoods. The SFA also provides opportunities for brands and retailers to contribute to broader capacity building and environmental work programs. Brands and retailers committing to a more responsible cashmere supply chain help to safeguard the high-quality reputation of the world’s most luxurious fibre and also help to safeguard the livelihoods of proud herding communities.

Written by: Sarah Krueger, Communications Manager, SFA